Last week, the Associated Press reported the story of Kristy Johnson, who is suing her father for sexually abusing her as a child. Melvin Kay Johnson, a well-respected Mormon educator, began assaulting his daughter when she was six years old and continued until she left home at eighteen. He inflicted the same abuse on her younger sisters, molesting his children with impunity for decades thanks to the protection of the Mormon church.

Kristy’s story is alarmingly familiar. After her father assaulted her regularly for most of her childhood, at 15, she reported the abuse to her bishop, who simply advised her father to “clean up his act.” When she and her sisters finally contacted police, church officials intervened to prevent her father’s arrest. What should have been a criminal case leading to a prison sentence was instead handled by a church court with no power beyond excommunication—and even that power it wielded with a gentle hand. Serial child abuser Melvin Kay Johnson didn’t lose his freedom; he simply lost his church membership, which was fully restored when the church welcomed him back after just a year. Kristy, however, was chastised for involving the police in a “church matter.”

My story echoes Kristy’s in many ways. My father assaulted me and other members of my Mormon family for decades. At 15 I reported my abuse to my high school guidance counselor, also a church leader. Instead of the proper authorities, he phoned my father, who beat me savagely when I arrived home. As a college student, I reported my abuse to the president of the Mormon church, who responded that men can’t help themselves, so it was up to me to keep them from sinning. Later, two family members took their abuse to the police, who made no arrest but turned both cases over to church courts. There, my father successfully argued that his victims had confused sexual assault with innocent affection. Punishment was dealt, however: the victims were publicly rebuked for soiling my father’s reputation.

Kristy Johnson is doing something truly vital for herself and her community: holding her father legally accountable. That’s possible now that Utah has eliminated the statute of limitations from child sexual abuse. Before 2016, survivors in Utah had to file suit by age 22, decades before most of us are able to face our abusers in court or even understand what happened to us. Because many states still require victims to file within a decade of turning 18, the Utah Legislature deserves credit for abolishing the statute of limitations. The new law is only a start, though, because the legislature hasn’t yet made it possible for Kristy Johnson to sue the other guilty party in her case: the Mormon church.

Kristy Johnson is doing something equally vital in telling her story. Her story is the basis of the lawsuit, of course, but she goes beyond that to tell her story in other ways. She’s the subject of a documentary film called Glass Temples, which has been shown in a couple of places and which I hope to see soon. She held a press conference to announce both the film and the lawsuit and told part of her story there, too, as she does on her excellent Facebook page. In sharing her story, she achieves two valuable goals, one obvious and one more subtle. Let’s start with the obvious.

Kristy’s story is helping people. At the very least, it stimulates discussion about the problem of childhood sexual abuse and the role of the Mormon church in enabling it. Alongside the video of her press conference, people on Facebook spoke up about their own traumatic histories in the church. Others educated skeptics who would challenge her story. Seizing on how much time had elapsed since Kristy’s abuse took place, for example, some skeptics claimed that the long delay made the abuse seem less serious or convincing. They soon learned that the opposite is true, that severe, persistent sexual abuse in childhood has such devastating physical, psychological, and social effects that survivors often need many years’ healing before they can talk publicly about their trauma.

Kristy’s ultimate goal in telling her story is reform. She wants the Mormon church held accountable so that it will stop protecting pedophiles and start protecting their victims. In her press conference, she called on President Russell M. Nelson to make the church a “beacon on a hill,” an example to other churches in the way it deals with child abuse. With this goal, I truly wish her luck, though my own experience makes me dubious. The church vests enormous power in untrained men whose impulses can claim the authority of divine revelation. It’s systemically hierarchical, with women and children in subordinate roles, not just in the days when patriarchs collected underage wives, but today. Despite its power and wealth, it sees itself as socially vulnerable, apt to be persecuted by outsiders and needful of vigilant self-defense, not the self-criticism essential for change. In my view, all of these features contribute to a culture that ignores or defends pious predators. I fear we will hear more stories like Kristy’s and mine.

That said, I think she’s doing a world of good because her story makes it easier for other Mormon survivors to tell their stories—and to be heard and believed when they do. In addition, her experience emphasizes the need for juvenile policies and programs independent of church influence. If that means stiffer penalties for educators, police officers, or social workers who allow the church to deal with suspected child abuse, then I’m all for that. Laws to penalize the church for usurping civil authority will also help, and legislators such as State Representative Angela Romero are working on them. In a recorded interview after Kristy’s story broke, she explained that such laws would prevent institutions from protecting abusers or failing to inform law enforcement about abuse cases. Such laws would finally allow Kristy to hold all of her abusers accountable. They would help my family and me, too.

The more subtle importance in Kristy’s story is what it’s likely doing for her. Storytelling is a vital tool in healing from childhood trauma, and it works in several ways. To begin with, it organizes the chaotic thoughts, feelings, images, and fragments of memory that survivors are left with. Telling a story requires imposing order: some form of chronology, some attribution of cause and effect. In fact, the more chaotic the original memories, the more people benefit psychologically from transforming those memories into coherent stories. One organizational principle is particularly crucial: the point of view we adopt toward our experience. In choosing a perspective from which to tell our stories—urgent and present-tense, for instance, or distant and ironic—we assert control over our experience. That assertion of control is fundamental to resilience.

During her press conference, Kristy told her story in small dramatic episodes, almost like tiny radio plays. Each story was mostly dialogue, with Kristy calmly repeating horrifying things people had said to her. For example, she described the church council that reinstated her father after his brief excommunication, as told to her by a bishop who was there. The council had asked her father to explain why he used his children for sex. His answer: because his wife did not fulfill his sexual needs. Expecting the bishop to condemn such a ludicrous answer, Kristy instead heard him call her father’s rationalization sympathetic and illuminating. “There wasn’t a dry eye in the room,” he added. “We knew and felt that he had repented.” Calmly repeating the bishop’s devastating lines, without comment or adornment, Kristy brought to life a toxic way of thinking in just a few words. It was storytelling of dignity, grace, and power, and I have no doubt that it was profoundly healing.

Another means of cultivating resilience is finding meaning in our experience. Kristy presents hers as a mandate to raise awareness and seek change, as I’ve already said. As importantly, she sees it as a bond with other survivors, especially those currently being abused. She spoke directly to them in her press conference, telling them “You are not alone,” and “You are loved.” She promised them she would do everything possible to “be your voice.” The meaning in her experience lies less its uniqueness than its commonality, its capacity to reflect and represent other people’s experience. Its unique details make it vivid and memorable, but its ultimate value lies in the features it shares with a thousand other stories of abuse.

In an earlier post, I wrote about resilience, the ability to cope successfully with childhood trauma. If you look at the list of actions and attitudes that produce resilience, you’ll see that nearly every one of them is on display in Kristy’s recent efforts. I’ve already mentioned that she assumed control over how she views her experience and found meaning in it. She has also worked to reinvent herself as an activist and spokesperson for abuse survivors. Her film is creative, and her legal efforts are optimistic about prospects for change within the Mormon church. Finally, she has joined—and is helping to expand—a community of survivors dedicated to ameliorating the abuse she suffered.

It’s not necessary that all survivors “go public” in the admirable way that Kristy has. I have struggled with that issue myself in writing Iron Legacy, a soon-to-be-published book that uses my own experience as an entry point to discussing childhood abuse and its adult consequences. In my case, the privacy of innocent people and the needs of my clients occasionally constrain what I can put into print–at least until I retire. But there are many different ways to develop and express resilience, some public, many more private. What’s important is finding meaning in some way, taking control in some way, seeking support in some way. In the end, we should look to Kristy as a powerful model and find our own paths toward the resilience she exemplifies so well.

Donna, thanks for sharing Kristy’s amazing story about childhood abuse, the trauma that carries into our adult lives and about the resilience that can occur. Thank you for being brave enough to reveal that you too were the victim of childhood abuse and institutional abuse by the Mormon Church. I can’t wait to read your upcoming book, “Iron Legacy”.

I have not stopped crying since I read this…such a beautiful validating newspost. It was exactly what I needed to see and read in the middle of the night when I couldn’t sleep. God truly is aware of dark moments and hears are prayers if only sometimes all we can do is groan in despair. I am so grateful for this beautiful uplifting informative piece. Thank you so very very much Donna J. Bevan-Lee, Ph.D. MSW. I think I can go to sleep now….seems like for now, all is well for me at this moment.

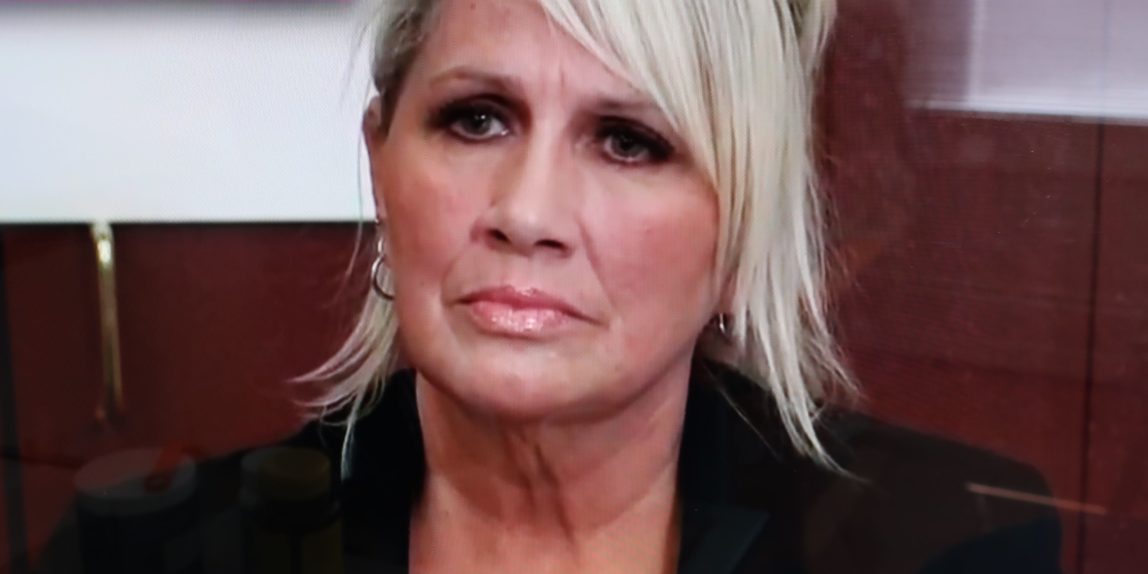

Kristy Johnson

Insightful and empathetic article. With Kristy all the way to victory.

Thank you so much Donna, for articulating how and why telling one’s story of abuse helps survivors heal. As a survivor of childhood sexual and physical abuse at the hands of my father, within the context of the Mormon church (1970’s-80’s), I can relate to the horror that you and Kristy endured.

As part of my continued healing, I was able to help pass that latest stature of limitation (SOL) reform law in Utah. SOLs are notoriously confusing, which is why survivors can become overwhelmed when after decades of healing, they dare to look into the laws in the place where the abuse occurred, to see whether they might have any legal remedy.

Regarding the Utah law you mention in your post- I just wanted to help specify what it does and doesn’t do: it changed the time survivors can get to CIVIL court (suing for restitution), but did NOT change anything for CRIMINAL courts (the abuser going to jail, etc.). So, in 2015, we were able to run and pass a bill that allowed people who at that time, were younger than 22 on the date it became law, to have all the time they need to get to CIVIL court. No more time limits for them.

Then, in 2016- we ran a bill to help all the people older than 22. That law gives those people until they are age 53 to get to CIVIL court- OR, if they were already 53 when the bill became law- then they had THREE YEARS from when the bill became law (in May of 2016) to get to court. This law is unique. Less than a dozen other states have passed a law like this. It is called window legislation- or a retroactive window. Up until this legislation was allowed, a survivor of childhood sexual abuse only had the amount of time to get to court that was on the law books when the abuse was occurring- notoriously short.

These windows allow the survivor to use the window of time in the present to bring an abuser to CIVIL court. Window legislation is not allowed when it comes to the CRIMINAL courts. The U.S. supreme court deemed it unconstitutional back in the early 2000’s after the state of California opened a retroactive window (survivors had ONE year to go to law enforcement about abuse in childhood, to see if they could get the state to bring CRIMINAL charges against people who abused them). During that ONE year, there were over 1,000 alleged abusers who had charges filed against them (many were Catholic priests/clergy) and about 300 of those were found guilty and sentenced.

To my mind, we need to eliminate CIVIL and CRIMINAL SOLs, going forward as well as backward in time, as part of stopping childhood sexual abuse from happening. If you or your readers are interested- you can visit the atty Marci Hamilton’s excellent website to see, at a glance, what each U.S. state and U.S. jurisdiction has currently in place regarding CIVIL and CRIMINAL SOLs for childhood sexual abuse at: http://www.sol-reform.com

Thank you so much for this valuable legal primer and for your role in making Utah law more fair and responsive to survivors. I’m impressed and moved by the way you find meaning and purpose in your difficult history, working to help others in similar situations–and, in time, to lessen the number of people with stories like ours. I’ll put Marci Hamilton’s website (which IS excellent) on my fledgling “Resources” page because, as you point out, social action can be a vital part of healing from abuse.

I wanted to thank you again for writing this. I am so very sorry for the horrendous abuse you endured and experienced. You are one brave soul. I so admire that you shared your story as well. When other survivors can bravely step forward and tell their stories then it empowers others to do the same and hopefully stops further abuse. Thank you again for all you wrote.

Kristy, I am so glad you saw my post! You truly are an inspiration to survivors of abuse generally and to me particularly as I begin to share my own story online and in print. I look forward to watching others step forward who would have remained silent and anguished were it not for your example.

From my own experience–and 40 years as a therapist–I know that a survivor’s healing journey can be long and challenging. If yours includes work on carried feelings, which often persist for decades despite great progress in self-understanding, I invite you to be my guest in a Legacy workshop, a description of which you can find on the page titled “The Legacy Center.” We generally have one workshop per month, so if your travels bring you up this way (Seattle area), I’d love to welcome you. If you get in touch by email, I can send more information.

Regardless, I look forward to the progress of your lawsuit and to the changes in public policy and public attitudes that it will surely inspire. I hope to see Glass Temples soon as well!

Kristy is a brave soul and I’m so proud of her standing strong. My heart hurts knowing that she was suffering and I knew nothing of her secret pain. I am so sorry. This was a beautiful article. I hope Kay is nervous, concerned and suffering from sleepless nights, he is truly a monster who tricked so many of us. The heavens heard and continue to hear your tears.I promise that God will destroy this monster who pretended to be a righteous man. I am so very sick over my not seeing that something was so very wrong in your life Kristy. Sending you love and supppprt from San Clemente cal

Can you please send this to a young Utah girl who went through exactly what Kristy did.

Send it to her by Facebook sharing. Her name is [deleted]!

Now there are at least five people named [deleted] on Facebook. This one has a Facebook profile picture with her and a horse with her boyfriend [deleted]. She is a [deleted] in Utah. Please send it to her right away to let her know she can press charges against her abusers. She states on Facebook that her brother raped her while her abusive adoptive mother blamed her by saying she ‘egged it on.” She also says her adoptive father touched her during her teen and pre teen years. Please send your story Kristy — along with the heartfelt replies. Maybe [deleted] wont feel so alone…

Nic, I would very much like to help your friend, but I need to clarify a couple of things. First, I am not Kristy Johnson; I’m the author of an article about her. Second, you can share the article and the replies, simply by forwarding the URL, which is:

https://stage6.breomedia.com/uncategorized/153/

Third, you may have noticed that I deleted your friend’s name and identifying information. You’re wonderful to care about her and want to help, but it’s important that she be the one who decides whether to publish her name in a forum such as this one. Some survivors, such as Kristy, choose to go public with their stories. Others prefer to keep their abuse histories private. Much as I admire Kristy and others for speaking out publicly, the choice must always lie with the person who experienced the trauma.

Thanks again for caring so much for your friend, and good luck to both of you.

I will right away snatch your rss as I can’t in finding your e-mail subscription link or

newsletter service. Do you have any? Please permit me recognise so that I may just subscribe.

Thanks.

I’m not yet set up for RSS, though I think it’s a great idea! When I do set it up, I will email you. Thanks for your interest.