Addiction in the pandemic is a large topic, so let me start with a single story—a story about relapse.

Richard and Sunny are a married couple with fourteen years of recovery between them. Richard’s recovery began in 2013 when he underwent treatment for sex addiction. A successful financial manager, he had for many years used his administrative skills to manage a double life, one devoted to work and family, the other devoted to sex with strangers, both prostitutes and women he met online. That divided life ended with an arrest for soliciting that damaged his career, nearly destroyed his marriage, and alienated his only child, prompting him to begin the long, difficult process of healing.

Richard’s wife Sunny had issues as well. She had been a busy studio singer in her twenties, providing backup vocals to a half-dozen famous pop songs, but had given up that career for marriage. Though initially content, she later began to experience anxiety and regret, a pervasive feeling that she must have made the wrong decision in giving up her career or she wouldn’t feel so bad in such an enviable life. When the anxiety flared into panic after her son started college, she added Xanax and Ambien to her daily wine regimen, though she kept her drug use under strict control until Richard’s arrest blew up that control, sending her into a downward spiral that landed her in treatment in 2014 and again in 2015. After a two-year separation to prioritize her own sobriety, Sunny rejoined Richard.

For years, all was well, and by “well,” I don’t mean “peachy” or “smooth” or “easy”; I mean that Richard and Sunny continued to work through past issues and learn new ways of relating to one another. Separately and together, they underwent therapy, not stopping until I suggested it might be time. They attended twelve-step meetings and found healthier ways to use the hours and the energy they had once devoted to their addictions. Sunny took her singing talents to a local theater group, appearing in a half-dozen musicals and launching a program to bring theater professionals to local high schools for performances and workshops. Richard took up kayaking and was soon touring with two friends from Sex Addicts Anonymous.

Then came the pandemic. At first, Richard and Sunny were simply grateful that Richard could work from home, that their home was spacious, and that no one they knew had died from Covid-19. But beneath the gratitude was a growing discomfort that they did not want to acknowledge. Barraged by news articles about overwhelmed hospitals, overwhelmed morgues, overwhelmed unemployment offices, and overwhelmed food banks, they felt petty for resenting the sacrifices imposed by lockdown, so they encouraged one another to keep an “attitude of gratitude” and to find online versions of their normal activities, especially the AA and SAA meetings that were so vital to their recovery. And, for a few months, that strategy worked, sort of.

But Sunny was soon struggling. More naturally social than Richard, her schedule was also hit harder by shutdowns as theaters closed and schools shifted to distance learning, which could barely manage math and history, much less theater workshops. By May, all she had on her calendar was one monthly board meeting and some birthday reminders. She tried to fill the gap by sewing masks and keeping the neighborhood food kiosk stocked and reading plays for when her high-school theater program resumed, but she started to feel a peculiar lethargy that made all of those things seem tedious and exhausting. She participated in Zoom calls and social events, as well as online meetings, but found them oddly enervating as well and soon began skipping them. With Richard shut in his home office most of the day, or out on longer and longer kayak expeditions, she felt both lonely and ashamed of feeling lonely, often rebuking herself on behalf of all the people in the world who were locked down by themselves. One day, sick of both her loneliness and her shame about it, she slipped a bottle of Grey Goose and a tin of Altoids into her grocery cart and began a slow slide back into addiction.

Behind his office door, Richard had his own struggles. His business had grown during the pandemic, which was great for him financially but less great psychologically. He tried to maintain a healthy work-life balance, yet the lockdown made him feel oddly claustrophobic, and work helped push that feeling away, so he worked most of the time. Kayaking also helped, but the local parks were all closed, giving him no place to put in without a long drive, which he felt guilty about. Something was up with Sunny, too. At first she had hovered a bit, dropping in to his office to suggest a walk, get his help with a task, or ask his opinion on a dinner idea, but now she spent most of her time in bed, reading or watching Netflix on her laptop. One night, after he emerged from an after-dinner Zoom call to find her asleep on the sofa, he covered her with a blanket then returned to his office, logged onto a web site he hadn’t visited for almost eight years, and began a slow slide back into his addiction.

A year into the pandemic, I’ve heard too many stories like this one, stories of people in recovery resuming active addiction. Though the newly sober have been particularly vulnerable, as the pandemic disrupts treatment and the building of vital support networks, many people with years of sober time have experienced a full relapse, a brief lapse, or, at the very least, intense cravings for their drug or compulsion of choice. Though there are zero statistics yet on relapse during the pandemic, Richard and Sunny are not alone; in fact, I know of addiction treatment professionals who have relapsed under the stress of the pandemic.

I have also heard stories of formerly light users of alcohol or cannabis or Etsy or Pornhub progressing to dependence, especially as the pandemic wore on. Under the pressure of lockdown—or the very different pressure of working on the front lines—what was once casual recreation became self-medication, a way to beat back loneliness, anxiety, boredom, and feelings of powerlessness. For this problem, we do have a little data, which suggests that the population of emerging addicts may be substantial, given the increase in problem drinking among people who previously drank in moderation, especially people whose workload was radically altered by the pandemic, a group that includes healthcare workers, mothers with children at home, and the newly unemployed. In fact, a national survey of healthcare workers by the Yale School of Medicine found that, after a year of coping with the pandemic, 42.8 percent of those polled met the criteria for an alcohol use disorder. We don’t have comparable statistics for other addictions, though anecdotal evidence hints that they’ll be equally alarming.

The third kind of story I’m hearing is about the pandemic making active addictions more severe, and a disquieting number of these stories end in death. In December, the Centers for Disease Control reported that fatal opioid overdoses were up 38.4 percent from last year. Just this week, the National Safety Council reported that, even with driving sharply curtailed by the pandemic, this year witnessed a rise in fatal car crashes caused by excessive speed and/or drug use, including alcohol use. Though, as before, there are no statistics on how the pandemic has affected other addictions, my colleagues and I have seen some dark changes in shopping addiction and sex addiction. Where compulsive shopping has migrated almost entirely online, making it possible to spend faster than ever before, sex addiction has, in some cases, migrated the other way with addicts who once relied on internet porn, webcams, and virtual sex beginning to seek out face-to-face contact, not in spite of the risk of contracting Covid-19 but because of it.

What’s going on? Why is the pandemic causing relapses, new addictions, and a worsening of existing addictions? To answer that question, we have to remember what addiction is, and I like the simple definition proposed by Dr. Daniel Sumrock, director of the Center for Addiction Sciences at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center’s College of Medicine: “ritualized, compulsive comfort-seeking.” People become vulnerable to addiction when they suffer trauma, whether in childhood, in adulthood, or both. For example, almost a quarter of the healthcare workers I just mentioned appear to be suffering from PTSD.

As I explained in an earlier blog post, childhood trauma makes people especially vulnerable to “ritualized, compulsive comfort-seeking” because it repeatedly overstimulates the brain’s alarm system. That system evolved to cope with threats to our survival, automatically flooding our bodies with hormones to help us run or fight for our lives. Because a parent’s rage, contempt, or indifference feels as threatening to children as a saber-tooth tiger, it automatically provokes the same fight-or-flight response, yet children can rarely discharge that energy by subduing the threat or running away, so it remains in the body. When that happens repeatedly, especially over many years, it results in a chronic state of high alert that is, at best, uncomfortable and, at worst, completely incapacitating. Addictions provide short-term relief, which is why they persist despite negative consequences.

But it’s not just our legacies from childhood that lead us to engage in “ritualized, compulsive comfort-seeking”; it’s also what’s happening in the world around us. Even before the pandemic, substance use disorders were rising in the US, especially in regions hard-hit by offshoring and automation. In fact, the years just before the pandemic saw such a dramatic rise in mortality from drug and alcohol use among working-class white Americans that, along with suicide, it reduced US life expectancy for three years in a row.[1] The cause was collective trauma: losing five million secure, well-paid manufacturing jobs and suffering the downstream effects of those losses, which damaged other businesses, local tax bases, family stability, and hope for the future. It happened so slowly that the media didn’t notice until opioid addiction became so severe they dubbed it an “epidemic,” but it was trauma nonetheless for the communities involved.

Covid-19 has been a different kind of collective trauma, more widespread, faster-moving, and definitely not ignored by the media. Its effects have varied dramatically, hitting harder in communities of color than in white communities, harder in poor communities than in wealthy communities, harder in New York than in Alaska. People’s experience of the last year has differed depending on whether they’re working at home, working in the community, or not working at all; whether they have children at home, are children at home, or can’t visit their children at home; whether they live alone or with companions; and, perhaps most importantly, whether they and their loved ones are sick or well. Different age groups experience the pandemic differently as well, with worrisome reports of widespread depression in young people, who are highly social and still in the process of forming the social networks that have helped older people cope with lockdown. But there are also some experiences most of us have in common, including fear of the virus,[2] anxiety about the future and about our ability to shape it, anger at losing our accustomed freedom, and loneliness, even if we live and/or work with other people.

Richard and Sunny had all those feelings, compounded by shame over having them. Because the pandemic didn’t inflict medical, professional, or financial hardship on them, they believed they weren’t entitled to feelings of distress; after all, the daily tally of new infections and deaths, the photos of plywood coffins lined up in mass graves and cars lined up at food banks, the heartbreaking interviews with overwhelmed health-care workers reminded them every day how fortunate they were. They felt real grief for the lives they had worked hard to build and for the community they loved, but they bright-sided it away—and not just out loud but in their heads as well. Because of their family histories, Sunny and Richard both found emotions challenging: Richard didn’t want any part of them while Sunny had trouble knowing what hers were, a condition known as alexithymia. Both had made great progress in recovery, but their original childhood trauma still exerted an influence, and the influence became much stronger under the collective trauma of the pandemic. Eventually, their unacknowledged distress became intolerable, and, like so many have during this pandemic, they reached for a familiar way to feel better.

End of part one. To read part two, click here.

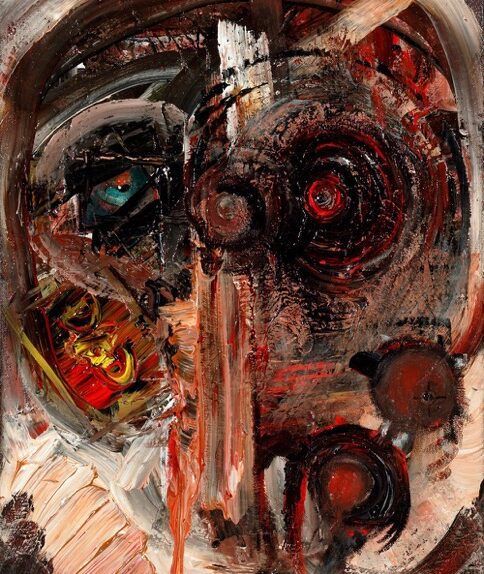

Image: “Intensive Care” by Charlie Lewis. Mr. Lewis’s work forms part of the Addiction and Art Exhibition and is covered by a Creative Commons license.

[1] Though I hotlinked news articles for readers’ ease, I strongly recommend the book that the articles are based on, Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism by Anne Case and Angus Deaton (a Nobel-prize-winning economist).

[2] I recognize that a percentage of the population claims to have (or acts as though they have) no fear of the virus, and I have no way to look inside their heads and see whether that’s true. I think it’s likely that most of them feel fear but also feel other emotions that are stronger than fear of the virus—for example, fear of economic losses, anger at being told what to do by the government, and love of the excitement that comes with risk.